-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

Asian markets rally with Wall St as rate hopes rise, AI fears ease

-

As US battles China on AI, some companies choose Chinese

As US battles China on AI, some companies choose Chinese

-

AI resurrections of dead celebrities amuse and rankle

-

Third 'Avatar' film soars to top in N. American box office debut

Third 'Avatar' film soars to top in N. American box office debut

-

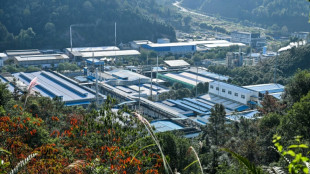

China's rare earths El Dorado gives strategic edge

-

Wheelchair user flies into space, a first

Wheelchair user flies into space, a first

-

French culture boss accused of mass drinks spiking to humiliate women

-

US Afghans in limbo after Washington soldier attack

US Afghans in limbo after Washington soldier attack

-

Nasdaq rallies again while yen falls despite BOJ rate hike

-

US university killer's mystery motive sought after suicide

US university killer's mystery motive sought after suicide

-

IMF approves $206 mn aid to Sri Lanka after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Rome to charge visitors for access to Trevi Fountain

Rome to charge visitors for access to Trevi Fountain

-

Stocks advance with focus on central banks, tech

-

Norway crown princess likely to undergo lung transplant

Norway crown princess likely to undergo lung transplant

-

France's budget hits snag in setback for embattled PM

-

Volatile Oracle shares a proxy for Wall Street's AI jitters

Volatile Oracle shares a proxy for Wall Street's AI jitters

-

Japan hikes interest rates to 30-year-high

-

Brazil's top court strikes down law blocking Indigenous land claims

Brazil's top court strikes down law blocking Indigenous land claims

-

'We are ghosts': Britain's migrant night workers

-

Asian markets rise as US inflation eases, Micron soothes tech fears

Asian markets rise as US inflation eases, Micron soothes tech fears

-

Trump signs $900 bn defense policy bill into law

-

EU-Mercosur deal delayed as farmers stage Brussels show of force

EU-Mercosur deal delayed as farmers stage Brussels show of force

-

Harrison Ford to get lifetime acting award

-

Trump health chief seeks to bar trans youth from gender-affirming care

Trump health chief seeks to bar trans youth from gender-affirming care

-

Argentine unions in the street over Milei labor reforms

-

Brazil open to EU-Mercosur deal delay as farmers protest in Brussels

Brazil open to EU-Mercosur deal delay as farmers protest in Brussels

-

Brussels farmer protest turns ugly as EU-Mercosur deal teeters

-

US accuses S. Africa of harassing US officials working with Afrikaners

US accuses S. Africa of harassing US officials working with Afrikaners

-

ECB holds rates as Lagarde stresses heightened uncertainty

-

Trump Media announces merger with fusion power company

Trump Media announces merger with fusion power company

-

Stocks rise as US inflation cools, tech stocks bounce

-

Zelensky presses EU to tap Russian assets at crunch summit

Zelensky presses EU to tap Russian assets at crunch summit

-

Danish 'ghetto' residents upbeat after EU court ruling

-

ECB holds rates but debate swirls over future

ECB holds rates but debate swirls over future

-

Bank of England cuts interest rate after UK inflation slides

-

Have Iran's authorities given up on the mandatory hijab?

Have Iran's authorities given up on the mandatory hijab?

-

British energy giant BP extends shakeup with new CEO pick

-

EU kicks off crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

EU kicks off crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

-

Sri Lanka plans $1.6 bn in cyclone recovery spending in 2026

-

Most Asian markets track Wall St lower as AI fears mount

Most Asian markets track Wall St lower as AI fears mount

-

Danish 'ghetto' tenants hope for EU discrimination win

-

What to know about the EU-Mercosur deal

What to know about the EU-Mercosur deal

-

Trump vows economic boom, blames Biden in address to nation

-

ECB set to hold rates but debate swirls over future

ECB set to hold rates but debate swirls over future

-

EU holds crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

-

Nasdaq tumbles on renewed angst over AI building boom

Nasdaq tumbles on renewed angst over AI building boom

-

Billionaire Trump nominee confirmed to lead NASA amid Moon race

-

CNN's future unclear as Trump applies pressure

CNN's future unclear as Trump applies pressure

-

German MPs approve 50 bn euros in military purchases

Scientists find chemical that stops locust cannibalism

Plagues of locusts that darken the skies and devastate all things that grow have been recorded since Biblical times, and today threaten the food security of millions of people across Asia and Africa.

But a new finding reported Thursday -- of a pheromone emitted by the insects to avoid being cannibalized when in a swarm -- could potentially pave the way to reining in the voracious pests.

Study leader Bill Hansson, director of the Max Planck Institute's Department of Evolutionary Neuroethology, told AFP that the new paper, published in Science, built on prior research that found swarms are directed not by cooperation -- but actually the threat of consumption by other locusts.

While repulsive to modern humans, cannibalism is rife in nature -- from lions that kill and devour cubs that are not theirs, to foxes that consume dead kin for energy.

For locusts, cannibalism is thought to serve an important ecological purpose.

Migratory locusts (Locusta migratoria) occur in different forms and behave so differently that they were, until recently, thought to be entirely different species.

Most of the time, they exist in a "solitary" phase keeping to themselves and eating comparatively little, like timid grasshoppers.

But when their population density increases due to rainfall and temporarily good breeding conditions, which is followed by food scarcity, they undergo major behavioral changes due to a rush of hormones that rev them up, causing them to aggregate in swarms and become more aggressive.

This is known as the "gregarious" phase and it's thought the fear of cannibalism helps keep the swarm moving in the same direction, from an area of lower to higher food concentration, according to 2020 research by Iain Couzin of the Max Planck Institute for Animal Research.

Hansson explained that "locusts eat each other from behind."

"So if you stop moving, you get eaten by the other, and that got us thinking that almost every animal who is under threat has some kind of countermeasure."

In painstaking experiments that took four years to complete, Hansson's team first established that cannibalism rates did indeed increase as the number of "gregarious" locusts kept in a cage went up, proving in the lab what Couzin had observed in the field in Africa (the triggering point was around 50 in a cage).

Next, they compared the odors emitted by solitary and gregarious locusts, finding 17 smells produced exclusively during the gregarious phase.

Of these, one chemical, known as phenylacetonitrile (PAN), was found to repel other locusts in behavioral tests.

PAN is involved in the synthesis of a potent toxin sometimes produced by gregarious locusts -- hydrogen cyanide -- so emitting PAN appeared to fit as the signal to tell others to back off.

- Genome editing -

To confirm the finding, they used CRISPR editing to genetically modify locusts so they could no longer produce PAN, which in turn made them more vulnerable to cannibalism.

For further confirmation, they tested dozens of the locusts' olfactory receptors, eventually landing on one that was very sensitive to PAN.

When they gene edited locusts to no longer produce this receptor, the modified locusts became more cannibalistic.

Writing in a related commentary in Science, researchers Iain Couzin and Einat Couzin-Fuchs said the discovery helped shed light on the "intricate balance" between the mechanisms that cause migratory locusts to group together versus compete with one another.

Future methods of locust control could therefore use technology that tips that delicate balance towards more competition, but Hansson cautioned: "You don't want to eradicate the species."

"If we could diminish the size of the swarms, steer them to areas where we are not growing our crops, then a lot could be gained," he added.

P.Kolisnyk--CPN