-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

What's at stake for Indian agriculture in Trump's trade deal?

-

Pakistan's capital picks concrete over trees, angering residents

Pakistan's capital picks concrete over trees, angering residents

-

Neglected killer: kala-azar disease surges in Kenya

-

Chile's climate summit chief to lead plastic pollution treaty talks

Chile's climate summit chief to lead plastic pollution treaty talks

-

Spain, Portugal face fresh storms, torrential rain

-

Opinions of Zuckerberg hang over social media addiction trial jury selection

Opinions of Zuckerberg hang over social media addiction trial jury selection

-

Crypto firm accidentally sends $40 bn in bitcoin to users

-

Dow surges above 50,000 for first time as US stocks regain mojo

Dow surges above 50,000 for first time as US stocks regain mojo

-

Danone expands recall of infant formula batches in Europe

-

EU nations back chemical recycling for plastic bottles

EU nations back chemical recycling for plastic bottles

-

Why bitcoin is losing its luster after stratospheric rise

-

Stocks rebound though tech stocks still suffer

Stocks rebound though tech stocks still suffer

-

Digital euro delay could leave Europe vulnerable, ECB warns

-

German exports to US plunge as tariffs exact heavy cost

German exports to US plunge as tariffs exact heavy cost

-

Stellantis takes massive hit for 'overestimation' of EV shift

-

'Mona's Eyes': how an obscure French art historian swept the globe

'Mona's Eyes': how an obscure French art historian swept the globe

-

In Dakar fishing village, surfing entices girls back to school

-

Russian pensioners turn to soup kitchen as war economy stutters

Russian pensioners turn to soup kitchen as war economy stutters

-

As Estonia schools phase out Russian, many families struggle

-

Toyota names new CEO, hikes profit forecasts

Toyota names new CEO, hikes profit forecasts

-

Bangladesh Islamist leader seeks power in post-uprising vote

-

Japan to restart world's biggest nuclear plant

Japan to restart world's biggest nuclear plant

-

UK royal finances in spotlight after Andrew's downfall

-

Undercover probe finds Australian pubs short-pouring beer

Undercover probe finds Australian pubs short-pouring beer

-

New Zealand deputy PM defends claims colonisation good for Maori

-

Amazon shares plunge as AI costs climb

Amazon shares plunge as AI costs climb

-

Deadly storm sparks floods in Spain, raises calls to postpone Portugal vote

-

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate, affirms auto sector's future is electric

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate, affirms auto sector's future is electric

-

Lower pollution during Covid boosted methane: study

-

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate

-

Record January window for transfers despite drop in spending

-

Mining giant Rio Tinto abandons Glencore merger bid

Mining giant Rio Tinto abandons Glencore merger bid

-

Davos forum opens probe into CEO Brende's Epstein links

-

ECB warns of stronger euro impact, holds rates

ECB warns of stronger euro impact, holds rates

-

Greece aims to cut queues at ancient sites with new portal

-

ECB holds interest rates as strong euro causes jitters

ECB holds interest rates as strong euro causes jitters

-

What does Iran want from talks with the US?

-

Wind turbine maker Vestas sees record revenue in 2025

Wind turbine maker Vestas sees record revenue in 2025

-

Bitcoin under $70,000 for first time since Trump's election

-

Germany claws back 59 mn euros from Amazon over price controls

Germany claws back 59 mn euros from Amazon over price controls

-

Germany claws back 70 mn euros from Amazon over price controls

-

Stock markets drop amid tech concerns before rate calls

Stock markets drop amid tech concerns before rate calls

-

BBVA posts record profit after failed Sabadell takeover

-

UN human rights agency in 'survival mode': chief

UN human rights agency in 'survival mode': chief

-

Greenpeace slams fossel fuel sponsors for Winter Olympics

-

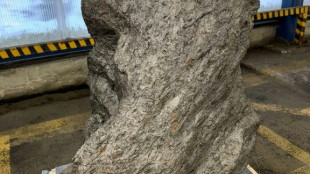

Russia says thwarted smuggling of giant meteorite to UK

Russia says thwarted smuggling of giant meteorite to UK

-

Heathrow still Europe's busiest airport, but Istanbul gaining fast

-

Shell profits climb despite falling oil prices

Shell profits climb despite falling oil prices

-

German factory orders rise at fastest rate in 2 years in December

Polar bear biopsies to shed light on Arctic pollutants

With one foot braced on the helicopter's landing skid, a veterinarian lifted his air rifle, took aim and fired a tranquiliser dart at a polar bear.

The predator bolted but soon slumped into the snowdrifts, its broad frame motionless beneath the Arctic sky.

The dramatic pursuit formed part of a pioneering research mission in Norway's Svalbard archipelago, where scientists, for the first time, took fat tissue biopsies from polar bears to study the impact of pollutants on their health.

The expedition came at a time when the Arctic region was warming at four times the global average, putting mounting pressure on the iconic predators as their sea-ice habitat shrank.

"The idea is to show as accurately as possible how the bears live in the wild -- but in a lab," Laura Pirard, a Belgian toxicologist, told AFP.

"To do this, we take their (fatty) tissue, cut it in very thin slices and expose it to the stresses they face, in other words pollutants and stress hormones," said Pirard, who developed the method.

Moments after the bear collapsed, the chopper circled back and landed. Researchers spilled out, boots crunching on the snow.

One knelt by the bear's flank, cutting thin strips of fatty tissue. Another drew blood.

Each sample was sealed and labelled before the bear was fitted with a satellite collar.

Scientists said that while the study monitors all the bears, only females were tracked with GPS collars as their necks are smaller than their heads -- unlike males, who cannot keep a collar on for more than a few minutes.

- Arctic lab -

For the scientists aboard the Norwegian Polar Institute's research vessel Kronprins Haakon, these fleeting encounters were the culmination of months of planning and decades of Arctic fieldwork.

In a makeshift lab on the icebreaker, samples remained usable for several days, subjected to controlled doses of pollutants and hormones before being frozen for further analysis back on land.

Each tissue fragment gave Pirard and her colleagues insight into the health of an animal that spent much of its life on sea ice.

Analysis of the fat samples showed that the main pollutants present were per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) -- synthetic chemicals used in industry and consumer goods that linger in the environment for decades.

Despite years of exposure, Svalbard's polar bears showed no signs of emaciation or ill health, according to the team.

The local population has remained stable or even increased slightly, unlike parts of Canada, where the Western Hudson Bay group declined by 27 percent between 2016 and 2021, from 842 to 618 bears, according to a government aerial survey.

Other populations in the Canadian Arctic, including the Southern Beaufort Sea, have also shown long-term declines linked to reduced prey access and longer ice-free seasons.

Scientists estimate there are around 300 polar bears in the Svalbard archipelago and roughly 2,000 in the broader region stretching from the North Pole to the Barents Sea.

The team found no direct link between sea ice loss and higher concentrations of pollutants in Svalbard's bears. Instead, differences in pollutant levels came down to the bears' diet.

Two types of bears -- sedentary and pelagic -- feed on different prey, leading to different chemicals building up in their bodies.

- Changing diet -

With reduced sea ice, the bears' diets have already started shifting, researchers said. These behavioural adaptations appeared to help maintain the population’s health.

"They still hunt seals but they also take reindeer (and) eggs. They even eat grass (seaweed), even though that has no energy for them," Jon Aars, the head of the Svalbard polar bear programme, told AFP.

"If they have very little sea ice, they necessarily need to be on land," he said, adding that they spend "much more time on land than they used to... 20 or 30 years ago".

This season alone, Aars and his team of marine toxicologists and spatial behaviour experts captured 53 bears, fitted 17 satellite collars, and tracked 10 mothers with cubs or yearlings.

"We had a good season," Aars said.

The team's innovations go beyond biopsies. Last year, they attached small "health log" cylinders to five females, recording their pulse and temperature.

Combined with GPS data, the devices offer a detailed record of how the bears roam, how they rest and what they endure.

Polar bears were once hunted freely across Svalbard but since an international protection agreement in 1976, the population here has slowly recovered.

The team's findings may help explain how the bears' world is changing, and at an alarming rate.

As the light faded and the icebreaker's engines hummed against the vast silence, the team packed away their tools, leaving the Arctic wilderness to its inhabitants.

X.Cheung--CPN