-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

Swiss court to hear landmark climate case against cement giant

-

Asian markets rally with Wall St as rate hopes rise, AI fears ease

Asian markets rally with Wall St as rate hopes rise, AI fears ease

-

As US battles China on AI, some companies choose Chinese

-

AI resurrections of dead celebrities amuse and rankle

AI resurrections of dead celebrities amuse and rankle

-

Third 'Avatar' film soars to top in N. American box office debut

-

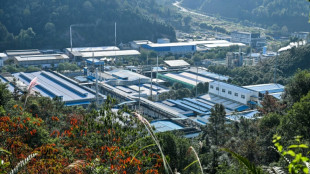

China's rare earths El Dorado gives strategic edge

China's rare earths El Dorado gives strategic edge

-

Wheelchair user flies into space, a first

-

French culture boss accused of mass drinks spiking to humiliate women

French culture boss accused of mass drinks spiking to humiliate women

-

US Afghans in limbo after Washington soldier attack

-

Nasdaq rallies again while yen falls despite BOJ rate hike

Nasdaq rallies again while yen falls despite BOJ rate hike

-

US university killer's mystery motive sought after suicide

-

IMF approves $206 mn aid to Sri Lanka after Cyclone Ditwah

IMF approves $206 mn aid to Sri Lanka after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Rome to charge visitors for access to Trevi Fountain

-

Stocks advance with focus on central banks, tech

Stocks advance with focus on central banks, tech

-

Norway crown princess likely to undergo lung transplant

-

France's budget hits snag in setback for embattled PM

France's budget hits snag in setback for embattled PM

-

Volatile Oracle shares a proxy for Wall Street's AI jitters

-

Japan hikes interest rates to 30-year-high

Japan hikes interest rates to 30-year-high

-

Brazil's top court strikes down law blocking Indigenous land claims

-

'We are ghosts': Britain's migrant night workers

'We are ghosts': Britain's migrant night workers

-

Asian markets rise as US inflation eases, Micron soothes tech fears

-

Trump signs $900 bn defense policy bill into law

Trump signs $900 bn defense policy bill into law

-

EU-Mercosur deal delayed as farmers stage Brussels show of force

-

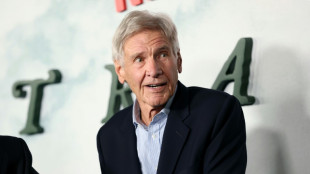

Harrison Ford to get lifetime acting award

Harrison Ford to get lifetime acting award

-

Trump health chief seeks to bar trans youth from gender-affirming care

-

Argentine unions in the street over Milei labor reforms

Argentine unions in the street over Milei labor reforms

-

Brazil open to EU-Mercosur deal delay as farmers protest in Brussels

-

Brussels farmer protest turns ugly as EU-Mercosur deal teeters

Brussels farmer protest turns ugly as EU-Mercosur deal teeters

-

US accuses S. Africa of harassing US officials working with Afrikaners

-

ECB holds rates as Lagarde stresses heightened uncertainty

ECB holds rates as Lagarde stresses heightened uncertainty

-

Trump Media announces merger with fusion power company

-

Stocks rise as US inflation cools, tech stocks bounce

Stocks rise as US inflation cools, tech stocks bounce

-

Zelensky presses EU to tap Russian assets at crunch summit

-

Danish 'ghetto' residents upbeat after EU court ruling

Danish 'ghetto' residents upbeat after EU court ruling

-

ECB holds rates but debate swirls over future

-

Bank of England cuts interest rate after UK inflation slides

Bank of England cuts interest rate after UK inflation slides

-

Have Iran's authorities given up on the mandatory hijab?

-

British energy giant BP extends shakeup with new CEO pick

British energy giant BP extends shakeup with new CEO pick

-

EU kicks off crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

-

Sri Lanka plans $1.6 bn in cyclone recovery spending in 2026

Sri Lanka plans $1.6 bn in cyclone recovery spending in 2026

-

Most Asian markets track Wall St lower as AI fears mount

-

Danish 'ghetto' tenants hope for EU discrimination win

Danish 'ghetto' tenants hope for EU discrimination win

-

What to know about the EU-Mercosur deal

-

Trump vows economic boom, blames Biden in address to nation

Trump vows economic boom, blames Biden in address to nation

-

ECB set to hold rates but debate swirls over future

-

EU holds crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

EU holds crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

-

Nasdaq tumbles on renewed angst over AI building boom

-

Billionaire Trump nominee confirmed to lead NASA amid Moon race

Billionaire Trump nominee confirmed to lead NASA amid Moon race

-

CNN's future unclear as Trump applies pressure

What are attoseconds? Nobel-winning physics explained

The Nobel Physics Prize was awarded on Tuesday to three scientists for their work on attoseconds, which are almost unimaginably short periods of time.

Their work using lasers gives scientists a tool to observe and possibly even manipulate electrons, which could spur breakthroughs in fields such as electronics and chemistry, experts told AFP.

- How fast are attoseconds? -

Attoseconds are a billionth of a billionth of a second.

To give a little perspective, there are around as many attoseconds in a single second as there have been seconds in the 13.8-billion year history of the universe.

Hans Jakob Woerner, a researcher at the Swiss university ETH Zurich, told AFP that attoseconds are "the shortest timescales we can measure directly".

- Why do we need such speed? -

Being able to operate on this timescale is important because these are the speeds at which electrons -- key parts of an atom -- operate.

For example, it takes electrons 150 attoseconds to go around the nucleus of a hydrogen atom.

This means the study of attoseconds has given scientists access to a fundamental process that was previously out of reach.

All electronics are mediated by the motion of electrons -- and the current "speed limit" is nanoseconds, Woerner said.

If microprocessors were switched to attoseconds, it could be possible to "process information a billion times faster," he added.

- How do you measure them? -

Franco-Swede physicist Anne L'Huillier, one of the three new Nobel laureates, was the first to discover a tool to pry open the world of attoseconds.

It involves using high-powered lasers to produce pulses of light for incredibly short periods.

Franck Lepine, a researcher at France's Institute of Light and Matter who has worked with L'Huillier, told AFP it was like "cinema created for electrons".

He compared it to the work of pioneering French filmmakers the Lumiere brothers, "who cut up a scene by taking successive photos".

John Tisch, a laser physics professor at Imperial College London, said that it was "like an incredibly fast, pulse-of-light device that we can then shine on materials to get information about their response on that timescale".

- How low can we go? -

All three of Tuesday's laureates at one point held the record for shortest pulse of light.

In 2001, French scientist Pierre Agostini's team managed to flash a pulse that lasted just 250 attoseconds.

L'Huillier's group beat that with 170 attoseconds in 2003.

In 2008, Hungarian-Austrian physicist Ferenc Krausz more than halved that number with an 80-attosecond pulse.

The current holder of the Guinness World Record for "shortest pulse of light" is Woerner's team, with a time of 43 attoseconds.

The time could go as low as a few attoseconds using current technology, Woerner estimated. But he added that this would be pushing it.

- What could the future hold? -

Technology taking advantage of attoseconds has largely yet to enter the mainstream, but the future looks bright, the experts said.

So far, scientists have mostly only been able to use attoseconds to observe electrons.

"But what is basically untouched yet -- or is just really beginning to be possible -- is to control" the electrons, to manipulate their motion, Woerner said.

This could lead to far faster electronics as well as potentially spark a revolution in chemistry.

So-called "attochemistry" could lead to more efficient solar cells, or even the use of light energy to produce clean fuels, he added.

D.Avraham--CPN