-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

Asian markets rally with Wall St as rate hopes rise, AI fears ease

-

As US battles China on AI, some companies choose Chinese

As US battles China on AI, some companies choose Chinese

-

AI resurrections of dead celebrities amuse and rankle

-

Third 'Avatar' film soars to top in N. American box office debut

Third 'Avatar' film soars to top in N. American box office debut

-

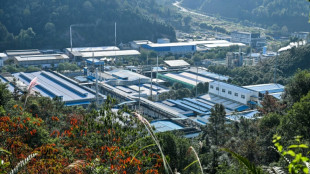

China's rare earths El Dorado gives strategic edge

-

Wheelchair user flies into space, a first

Wheelchair user flies into space, a first

-

French culture boss accused of mass drinks spiking to humiliate women

-

US Afghans in limbo after Washington soldier attack

US Afghans in limbo after Washington soldier attack

-

Nasdaq rallies again while yen falls despite BOJ rate hike

-

US university killer's mystery motive sought after suicide

US university killer's mystery motive sought after suicide

-

IMF approves $206 mn aid to Sri Lanka after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Rome to charge visitors for access to Trevi Fountain

Rome to charge visitors for access to Trevi Fountain

-

Stocks advance with focus on central banks, tech

-

Norway crown princess likely to undergo lung transplant

Norway crown princess likely to undergo lung transplant

-

France's budget hits snag in setback for embattled PM

-

Volatile Oracle shares a proxy for Wall Street's AI jitters

Volatile Oracle shares a proxy for Wall Street's AI jitters

-

Japan hikes interest rates to 30-year-high

-

Brazil's top court strikes down law blocking Indigenous land claims

Brazil's top court strikes down law blocking Indigenous land claims

-

'We are ghosts': Britain's migrant night workers

-

Asian markets rise as US inflation eases, Micron soothes tech fears

Asian markets rise as US inflation eases, Micron soothes tech fears

-

Trump signs $900 bn defense policy bill into law

-

EU-Mercosur deal delayed as farmers stage Brussels show of force

EU-Mercosur deal delayed as farmers stage Brussels show of force

-

Harrison Ford to get lifetime acting award

-

Trump health chief seeks to bar trans youth from gender-affirming care

Trump health chief seeks to bar trans youth from gender-affirming care

-

Argentine unions in the street over Milei labor reforms

-

Brazil open to EU-Mercosur deal delay as farmers protest in Brussels

Brazil open to EU-Mercosur deal delay as farmers protest in Brussels

-

Brussels farmer protest turns ugly as EU-Mercosur deal teeters

-

US accuses S. Africa of harassing US officials working with Afrikaners

US accuses S. Africa of harassing US officials working with Afrikaners

-

ECB holds rates as Lagarde stresses heightened uncertainty

-

Trump Media announces merger with fusion power company

Trump Media announces merger with fusion power company

-

Stocks rise as US inflation cools, tech stocks bounce

-

Zelensky presses EU to tap Russian assets at crunch summit

Zelensky presses EU to tap Russian assets at crunch summit

-

Danish 'ghetto' residents upbeat after EU court ruling

-

ECB holds rates but debate swirls over future

ECB holds rates but debate swirls over future

-

Bank of England cuts interest rate after UK inflation slides

-

Have Iran's authorities given up on the mandatory hijab?

Have Iran's authorities given up on the mandatory hijab?

-

British energy giant BP extends shakeup with new CEO pick

-

EU kicks off crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

EU kicks off crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

-

Sri Lanka plans $1.6 bn in cyclone recovery spending in 2026

-

Most Asian markets track Wall St lower as AI fears mount

Most Asian markets track Wall St lower as AI fears mount

-

Danish 'ghetto' tenants hope for EU discrimination win

-

What to know about the EU-Mercosur deal

What to know about the EU-Mercosur deal

-

Trump vows economic boom, blames Biden in address to nation

-

ECB set to hold rates but debate swirls over future

ECB set to hold rates but debate swirls over future

-

EU holds crunch summit on Russian asset plan for Ukraine

-

Nasdaq tumbles on renewed angst over AI building boom

Nasdaq tumbles on renewed angst over AI building boom

-

Billionaire Trump nominee confirmed to lead NASA amid Moon race

-

CNN's future unclear as Trump applies pressure

CNN's future unclear as Trump applies pressure

-

German MPs approve 50 bn euros in military purchases

Grandma chimps offer clues for evolution of menopause in humans

Humans and some whales are the only known species in which females live long after they stop being able to reproduce.

A new paper in the journal Science on Thursday argues that chimpanzees should now be added to the list, and offers clues about the evolutionary imperatives behind menopause in women.

"Chimpanzees have been studied in the wild for a long time, and you might think there's nothing left to learn about them," senior author Kevin Langergraber of Arizona State University told AFP. "I think this research shows us that's not true."

The vast majority of mammal females produce offspring until the end of their lives, but humans experience a decline in reproductive hormones and the permanent cessation of ovary function around age 50.

Females of five species of toothed whale, including orcas and narwhals, similarly survive well beyond fertile age.

It isn't obvious why natural selection would favor this trait, and only among a handful of species.

Some scientists have put forward the "grandmother hypothesis" as a possible explanation: the idea that older females enter a post-reproductive state to consume fewer resources and focus on improving their grandchildren's odds of survival.

- Demographics and hormones -

In the new paper, researchers examined the mortality and fertility rates of 185 female chimpanzees in the Ngogo community of wild chimpanzees in Kibale National Park, Uganda, between 1995 and 2016.

Specifically, the team calculated a metric called the post-reproductive representation (PrR), which is the average proportion of the adult life span that is spent in a post-reproductive state.

Past attempts that used demographic data to study whether chimps underwent menopause were hampered by haphazard statistical methods, lead author Brian Wood of the University of California, Los Angeles, told AFP, with PrR proving a more robust measure.

It showed Ngogo chimpanzee females -- but not other chimpanzees from other populations -- lived on average 20 percent of their adult years in a post-reproductive state, just a little under what has been observed in humans.

To exclude the possibility that, say, an STD swept through the community causing mass sterility among older females in the past, the team paired the demographic data with hormonal status.

They took urine samples of 66 females ranging in age and reproductive status, and measured the levels of gonadotropins, estrogens, and progestins, finding the hormonal patterns closely mirrored what was seen in human females experiencing menopausal transition.

- Chimps aren't good grandmas -

Still, the case for menopause in chimps isn't quite closed, say the authors, offering two possible interpretations.

Wild animals have been found to have substantial post-reproductive life spans in captivity where they are protected from predators and disease, and it's possible the Ngogo chimps similarly experienced unusually favorable conditions, such as an absence of leopards that were hunted to extinction in the area.

Alternatively, the remote Ngogo chimps might be more typical of historic populations that were untouched by human activities such as hunting and logging.

If that's so, said Wood, then scientists need to update their evolutionary theories of menopause.

In chimpanzee society, daughters leave the community in which they are born, while the males who remain mate promiscuously.

That means males don't know who their offspring are, and by extension, grandmothers don't know which grandoffspring are theirs -- so the "grandmother hypothesis" won't apply.

Instead, Wood said that menopause might have evolved to reduce competition for limited breeding opportunities between aging females and their daughters.

When a female chimp first enters a new group, she starts out with a low level of relatedness to other members, though this increases over time as she breeds.

Since her genes are by then widespread, she has less to gain in breeding conflict against a younger female.

Dan Franks of the University of York who has studied postmenopausal killer whales, described the study as "fascinating".

"This research presents the first instance of menopause occurring in non-human primates in the wild," he said, adding that the second interpretation offered by the authors was "tantalizing" in terms of its evolutionary implications.

The authors hope to study the question further among bonobos, who along with chimpanzees are our closest relatives in the animal kingdom.

P.Gonzales--CPN