-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

Ghana moves to rewrite mining laws for bigger share of gold revenues

-

Russia's sanctioned oil firm Lukoil to sell foreign assets to Carlyle

Russia's sanctioned oil firm Lukoil to sell foreign assets to Carlyle

-

Gold soars towards $5,600 as Trump rattles sabre over Iran

-

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

-

Vietnam and EU upgrade ties as EU chief visits Hanoi

-

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

-

Gold soars past $5,500 as Trump sabre rattles over Iran

-

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

-

China's ambassador warns Australia on buyback of key port

-

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

-

Venezuelans eye economic revival with hoped-for oil resurgence

-

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

-

French Senate adopts bill to return colonial-era art

-

Tesla profits tumble on lower EV sales, AI spending surge

Tesla profits tumble on lower EV sales, AI spending surge

-

Meta shares jump on strong earnings report

-

Anti-immigration protesters force climbdown in Sundance documentary

Anti-immigration protesters force climbdown in Sundance documentary

-

Springsteen releases fiery ode to Minneapolis shooting victims

-

SpaceX eyes IPO timed to planet alignment and Musk birthday: report

SpaceX eyes IPO timed to planet alignment and Musk birthday: report

-

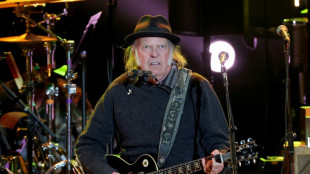

Neil Young gifts music to Greenland residents for stress relief

-

Fear in Sicilian town as vast landslide risks widening

Fear in Sicilian town as vast landslide risks widening

-

King Charles III warns world 'going backwards' in climate fight

-

Court orders Dutch to protect Caribbean island from climate change

Court orders Dutch to protect Caribbean island from climate change

-

Rules-based trade with US is 'over': Canada central bank head

-

Holocaust survivor urges German MPs to tackle resurgent antisemitism

Holocaust survivor urges German MPs to tackle resurgent antisemitism

-

'Extraordinary' trove of ancient species found in China quarry

-

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

-

UK proposes to let websites refuse Google AI search

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran threatens tough response

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran threatens tough response

-

Germany cuts growth forecast as recovery slower than hoped

-

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

-

Greenland dispute is 'wake-up call' for Europe: Macron

-

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

-

Sweden plans to ban mobile phones in schools

-

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

-

Susan Sarandon to be honoured at Spain's top film awards

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

-

Spain eyes full service on train tragedy line in 10 days

-

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

-

SKorean chip giant SK hynix posts record operating profit for 2025

-

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

-

Uganda's Quidditch players with global dreams

-

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

-

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

-

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

-

Minnesota congresswoman unbowed after attacked with liquid

-

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

-

Omar attacked in Minneapolis after Trump vows to 'de-escalate'

-

Dollar struggles to recover from losses after Trump comments

Dollar struggles to recover from losses after Trump comments

-

Greenland blues to Delhi red carpet: EU finds solace in India

Forget mammoths, study shows how to resurrect Christmas Island rats

Ever since the movie Jurassic Park, the idea of bringing extinct animals back to life has captured the public's imagination -- but what might scientists turn their attention towards first?

Instead of focusing on iconic species like the woolly mammoth or the Tasmanian tiger, a team of paleogeneticists have studied how, using gene editing, they could resurrect the humble Christmas Island rat, which died out around 120 years ago.

Though they did not follow through and create a living specimen, they say their paper, published in Current Biology on Wednesday, demonstrates just how close scientists working on de-extinction projects could actually get using current technology.

"I am not doing de-extinction, but I think it's a really interesting idea, and technically it's really exciting," senior author Tom Gilbert, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Copenhagen, told AFP.

There are three pathways to bringing back extinct animals: back-breeding related species to achieve lost traits; cloning, which was used to create Dolly the sheep in 1996; and finally genetic editing, which Gilbert and colleagues looked at.

The idea is to take surviving DNA of an extinct species, and compare it to the genome of a closely-related modern species, then use techniques like CRISPR to edit the modern species' genome in the places where it differs.

The edited cells could then be used to create an embryo implanted in a surrogate host.

Gilbert said old DNA was like a book that has gone through a shredder, while the genome of a modern species is like an intact "reference book" that can be used to piece together the fragments of its degraded counterpart.

His interest in Christmas Island rats was piqued when a colleague studied their skins to look for evidence of pathogens that caused their extinction around 1900.

It's thought that black rats brought on European ships wiped out the native species, described in an 1887 entry of the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London as a "fine new Rat," large in size with a long yellow-tipped tail and small rounded ears.

- Key functions lost -

The team used brown rats, commonly used in lab experiments, as the modern reference species, and found they could reconstruct 95 percent of the Christmas Island rat genome.

That may sound like a big success, but the five percent they couldn't recover was from regions of the genome that controlled smell and immunity, meaning that the recovered rat might look the same but would lack key functionality.

"The take home is, even if we have basically the perfect ancient DNA situation, we've got a really good sample, we've sequenced the hell out of it, we're still lacking five percent of it," said Gilbert.

The two species diverged around 2.6 million years ago: close in evolutionary time, but not close enough to fully reconstruct the lost species' full genome.

This has important implications for de-extinction efforts, such as a project by US bioscience firm Colossal to resurrect the mammoth, which died out around 4,000 years ago.

Mammoths have roughly the same evolutionary distance from modern elephants as brown rats and Christmas Island rats.

Teams in Australia meanwhile are looking at reviving the Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, whose last surviving member died in captivity in 1936.

Even if gene-editing were perfected, replica animals created with the technique would thus have certain critical deficiencies.

"Let's say you're bringing back a mammoth solely to have a hairy elephant in a zoo to raise money or get conservation awareness -- it doesn't really matter," he said.

But if the goal is to bring back the animal in its exact original form "that's never going to happen," he said.

Gilbert admitted that, while the science was fascinating, he had mixed feelings on de-extinction projects.

"I'm not convinced it is the best use of anyone's money," he said. "If you had to choose between bringing back something or protecting what was left, I'd put my money into protection."

A.Samuel--CPN