-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

Ghana moves to rewrite mining laws for bigger share of gold revenues

-

Russia's sanctioned oil firm Lukoil to sell foreign assets to Carlyle

Russia's sanctioned oil firm Lukoil to sell foreign assets to Carlyle

-

Gold soars towards $5,600 as Trump rattles sabre over Iran

-

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

-

Vietnam and EU upgrade ties as EU chief visits Hanoi

-

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

-

Gold soars past $5,500 as Trump sabre rattles over Iran

-

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

-

China's ambassador warns Australia on buyback of key port

-

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

-

Venezuelans eye economic revival with hoped-for oil resurgence

-

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

-

French Senate adopts bill to return colonial-era art

-

Tesla profits tumble on lower EV sales, AI spending surge

Tesla profits tumble on lower EV sales, AI spending surge

-

Meta shares jump on strong earnings report

-

Anti-immigration protesters force climbdown in Sundance documentary

Anti-immigration protesters force climbdown in Sundance documentary

-

Springsteen releases fiery ode to Minneapolis shooting victims

-

SpaceX eyes IPO timed to planet alignment and Musk birthday: report

SpaceX eyes IPO timed to planet alignment and Musk birthday: report

-

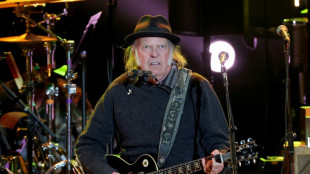

Neil Young gifts music to Greenland residents for stress relief

-

Fear in Sicilian town as vast landslide risks widening

Fear in Sicilian town as vast landslide risks widening

-

King Charles III warns world 'going backwards' in climate fight

-

Court orders Dutch to protect Caribbean island from climate change

Court orders Dutch to protect Caribbean island from climate change

-

Rules-based trade with US is 'over': Canada central bank head

-

Holocaust survivor urges German MPs to tackle resurgent antisemitism

Holocaust survivor urges German MPs to tackle resurgent antisemitism

-

'Extraordinary' trove of ancient species found in China quarry

-

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

-

UK proposes to let websites refuse Google AI search

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran threatens tough response

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran threatens tough response

-

Germany cuts growth forecast as recovery slower than hoped

-

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

-

Greenland dispute is 'wake-up call' for Europe: Macron

-

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

-

Sweden plans to ban mobile phones in schools

-

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

-

Susan Sarandon to be honoured at Spain's top film awards

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

-

Spain eyes full service on train tragedy line in 10 days

-

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

-

SKorean chip giant SK hynix posts record operating profit for 2025

-

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

-

Uganda's Quidditch players with global dreams

-

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

-

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

-

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

-

Minnesota congresswoman unbowed after attacked with liquid

-

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

-

Omar attacked in Minneapolis after Trump vows to 'de-escalate'

-

Dollar struggles to recover from losses after Trump comments

Dollar struggles to recover from losses after Trump comments

-

Greenland blues to Delhi red carpet: EU finds solace in India

Can a giant seawall save Indonesia's disappearing coast?

The encroaching ocean laps against a road in Karminah's village, threatening her home on Indonesia's Java island, where the government says it has a plan to hold back the tide.

It wants to build an $80-billion, 700-kilometre (435-mile) seawall along Java's coast to tackle land loss as climate change lifts sea levels and groundwater extraction prompts land to sink.

For residents who have seen the tide come more than a kilometre inland in parts of Java, the plan sounds like salvation.

But with a timeline of decades and uncertain financing, it looks unlikely to arrive quickly enough, and climate experts warn it could make matters worse by pushing erosion elsewhere and disrupting ecosystems.

For Karminah, 50, those concerns feel distant.

"What's important is that it doesn't flood here. So that it's comfortable," she told AFP in Bedono village, referring to a coastal road that disappears almost daily.

"School can't happen, the children can't play, they can only sit on the pavement staring at the water."

The government calls the colossal wall one of its "most vital" initiatives to help coastal communities in Java, which houses more than half of Indonesia's 280 million citizens, as well as fast-sinking capital Jakarta.

Bedono residents like village chief Muhammad Syarif currently elevate their homes with clay soil but say a seawall is "very much needed" to avert disaster.

"It is the right solution because the coastline needs wave management," he said.

Funding remains uncertain, though President Prabowo Subianto has urged Asian and Middle Eastern investment.

This week, he inaugurated a new agency to oversee the project.

"I don't know which president will finish it, but we will start it," Prabowo said in June.

- Abandoned villages -

Seawalls and other coastal fortifications have been used globally to keep damaging tides at bay.

In Japan, fortress-like barriers were installed in some places after the 2011 earthquakes and tsunami, while the Netherlands relies on a system of hill-like dikes to stay dry.

Such fortifications absorb and deflect wave energy, protecting coastal infrastructure and populations.

But Indonesia's needs are urgent, with one to 20 centimetres (0.4 to eight inches) of land disappearing along Java's northern coast annually.

Large areas will vanish by 2100 on the current climate change trajectory, according to environmental non-profit Climate Central.

The fortifications can also have negative consequences, destroying beaches, pushing erosion seaward, and disrupting ecosystems and fishing communities.

In places like Puerto Rico and New Caledonia, seawalls have collapsed under the constant beat of waves, which also erode sand below.

"They come at considerable environmental and social cost," said Melanie Bishop, professor at Australia's Macquarie University.

"Their construction leads to loss of shoreline habitat and they impede movement of both animals and people between land and sea," the coastal ecologist said.

A 2022 UN report warned seawalls only offer a temporary fix and can even worsen climate change effects.

For Indonesian crab farmer Rasjoyo, coastal erosion is not a theoretical problem.

He and hundreds more once lived in now-abandoned Semonet village, where seawater laps into evacuated homes. It now lies a 20-minute boat ride from land.

"The floods were getting worse. The house was sinking. Every month, the change was drastic," the 38-year-old told AFP.

He says the seawall -- first proposed in 1995 -- will come too late.

"If it happens, when will it arrive here? In what year?" he asked.

"It might not be very effective either, because the land has already subsided."

- 'Find a solution' -

Some climate experts believe nature-based solutions like mangroves and reefs would be better alternatives.

"Unlike seawalls that would need to be upgraded as sea levels rise, these habitats accrete vertically," said Bishop.

"In some instances this vertical accretion can keep pace with sea level rise."

Another alternative could be a mixture of relocations and more targeted, limited seawalls, said Heri Andreas, a land subsidence expert at the Bandung Institute of Technology.

"The win-win solution is a partial or segmented seawall," he said, describing the current proposal as like "killing a duck with a bazooka".

"It is more effective if we do relocation. And then in some parts, maybe only a coastal dike or elevating the coastal infrastructure would be enough."

He hopes to persuade Prabowo's administration to switch course before the mega-project begins.

"We need more listening," he said. "It's a bit better than before, but it's not enough yet."

In Bedono, where a cemetery was recently relocated to save it from the waves, residents simply want a fast fix.

"The solution is to build something, I don't know, just build a road, a dike or a coastal belt so it doesn't keep happening," said Karminah.

"What can we do?" she added. "Please help me find a solution so the water doesn't rise."

A.Zimmermann--CPN