-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

Vietnam and EU upgrade ties as EU chief visits Hanoi

-

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

-

Gold soars past $5,500 as Trump sabre rattles over Iran

-

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

-

China's ambassador warns Australia on buyback of key port

-

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

-

Venezuelans eye economic revival with hoped-for oil resurgence

-

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

-

French Senate adopts bill to return colonial-era art

-

Tesla profits tumble on lower EV sales, AI spending surge

Tesla profits tumble on lower EV sales, AI spending surge

-

Meta shares jump on strong earnings report

-

Anti-immigration protesters force climbdown in Sundance documentary

Anti-immigration protesters force climbdown in Sundance documentary

-

Springsteen releases fiery ode to Minneapolis shooting victims

-

SpaceX eyes IPO timed to planet alignment and Musk birthday: report

SpaceX eyes IPO timed to planet alignment and Musk birthday: report

-

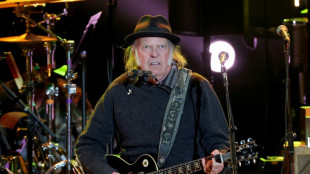

Neil Young gifts music to Greenland residents for stress relief

-

Fear in Sicilian town as vast landslide risks widening

Fear in Sicilian town as vast landslide risks widening

-

King Charles III warns world 'going backwards' in climate fight

-

Court orders Dutch to protect Caribbean island from climate change

Court orders Dutch to protect Caribbean island from climate change

-

Rules-based trade with US is 'over': Canada central bank head

-

Holocaust survivor urges German MPs to tackle resurgent antisemitism

Holocaust survivor urges German MPs to tackle resurgent antisemitism

-

'Extraordinary' trove of ancient species found in China quarry

-

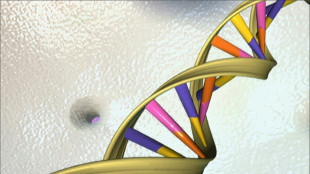

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

-

UK proposes to let websites refuse Google AI search

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran threatens tough response

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran threatens tough response

-

Germany cuts growth forecast as recovery slower than hoped

-

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

-

Greenland dispute is 'wake-up call' for Europe: Macron

-

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

-

Sweden plans to ban mobile phones in schools

-

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

-

Susan Sarandon to be honoured at Spain's top film awards

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

-

Spain eyes full service on train tragedy line in 10 days

-

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

-

SKorean chip giant SK hynix posts record operating profit for 2025

-

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

-

Uganda's Quidditch players with global dreams

-

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

-

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

-

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

-

Minnesota congresswoman unbowed after attacked with liquid

-

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

-

Omar attacked in Minneapolis after Trump vows to 'de-escalate'

-

Dollar struggles to recover from losses after Trump comments

Dollar struggles to recover from losses after Trump comments

-

Greenland blues to Delhi red carpet: EU finds solace in India

-

French ex-senator found guilty of drugging lawmaker

French ex-senator found guilty of drugging lawmaker

-

US Fed set to pause rate cuts as it defies Trump pressure

-

Trump says will 'de-escalate' in Minneapolis after shooting backlash

Trump says will 'de-escalate' in Minneapolis after shooting backlash

-

CERN chief upbeat on funding for new particle collider

'Missing' Ukrainian children prepare to join Polish schools

Children returning to school in Poland next week will find a new group of classmates -- Ukrainian children now living in the country who were not previously enrolled in the Polish education system.

A new law making education compulsory for refugee families is coming into force but nobody knows exactly how many children will enrol, with estimates ranging from 20,000 to 80,000.

"We are still in limbo," said Maryna Rud, the mother of 12-year-old Nadia, who left Ukraine at the outset of the Russian invasion in 2022.

Rud enrolled her daughter in a Polish school but said she suffered months of bullying and she eventually took her out.

"They laughed at her incorrect pronunciation. She would tell me: 'I say a word, they laugh, I say a word, they laugh'," Maryna recounted.

Nadia spent the last year studying online in a Ukrainian school, a solution still relied on by many refugee families.

- 'Missing in Poland' -

Exactly how many children are unaccounted for in the Polish education system "is a great unknown," said Jedrzej Witkowski, head of the Centre for Citizenship Education, a nonprofit group.

In the weeks after Moscow launched its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Poland opened its borders to shelter refugees and the European Union granted them the right to move freely across the bloc.

"It's very hard to monitor," Witkowski said. "We are unable to say exactly how many schoolchildren, or more broadly, how many Ukrainian citizens, have taken refuge in Poland and how many still remain in our country."

Around 134,000 Ukrainian children attended Polish schools before the summer holidays.

The Centre for Citizenship Education estimated that 20,000 to 80,000 children have so far been outside the education system.

In the "best case scenario", Witkowski said, the children have been following lessons remotely.

That was the case for Ivan, a 12-year-old who moved to Poland with his mother, Nataliya Khotsinovska, right after the invasion.

Ivan has been learning Polish during the summer, but for now, his mother chose to send him to a private Ukrainian school, a solution she calls "a soft transition period".

"We have no friends here, no one to communicate with," Khotsinovska told AFP.

"It's also hard for mothers... Sometimes you hesitate between the result of learning and the child's peace of mind," Khotsinovska said.

- Fly swatters -

Her son participated in a series of language courses and integration activities run by the Catholic Intelligentsia Club (KIK) in Warsaw.

The project, called "Trampoline", is designed to help Ukrainian children -- and their parents -- with the transition.

The courses show "how to respond to bullying, to teach parents how to act," said Olesya Kolisnyk, one of the organisers.

"Ninety-nine percent have problems with bullying," Kolisnyk told AFP, echoing experts' warnings that it is one of two major problems for Ukrainian children, alongside the language barrier.

To help with the latter, Homo Faber, a nonprofit from the city of Lublin, began offering language courses for Ukrainians who start learning in Polish schools.

Sitting around a table, a group of seven children meticulously practise tracing the letter "c" before being handed fly swatters to tap cards depicting objects starting with that letter.

Paulina Skrzypek, teacher of the seven to nine-year-olds age group, said that Polish and Ukrainian bear similarities, but that does not necessarily work in refugee children's favour.

"We have those so-called 'false friends', and kids think that in Polish something sounds the same as in Ukrainian, but it turns out it doesn't," she said.

- 'Has Putin died?' -

To Danuta Kozakiewicz, headmistress of a Warsaw primary school, language plays a crucial role in how Ukrainian children get along with their Polish peers.

Kozakiewicz also organises various integration events, from football tournaments to school trips.

"During a football match, one kid is shouting in Polish, the other in Ukrainian, but they somehow know what's going on -- and they play for the same team," she said, laughing.

But problems remain, especially when the Ukrainian children suddenly disappear when their parents decided to return to Ukraine or relocate to another country without notifying the school.

Returning home is what many Ukrainian schoolchildren in Poland still yearn for.

"They check social media every day and see what's going on. 'What's the news, has Putin died?'" Maryna Rud said.

"They are constantly waiting, every day, for that moment of coming back home."

Y.Ponomarenko--CPN