-

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

Kenya's economy faces climate change risks: World Bank

-

EU eyes migration clampdown with push on deportations, visas

-

Northern Mozambique: massive gas potential in an insurgency zone

Northern Mozambique: massive gas potential in an insurgency zone

-

Gold demand hits record high on Trump policy doubts: industry

-

UK drugs giant AstraZeneca announces $15 bn investment in China

UK drugs giant AstraZeneca announces $15 bn investment in China

-

Ghana moves to rewrite mining laws for bigger share of gold revenues

-

Russia's sanctioned oil firm Lukoil to sell foreign assets to Carlyle

Russia's sanctioned oil firm Lukoil to sell foreign assets to Carlyle

-

Gold soars towards $5,600 as Trump rattles sabre over Iran

-

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

-

Vietnam and EU upgrade ties as EU chief visits Hanoi

-

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

Hongkongers snap up silver as gold becomes 'too expensive'

-

Gold soars past $5,500 as Trump sabre rattles over Iran

-

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

Samsung logs best-ever profit on AI chip demand

-

China's ambassador warns Australia on buyback of key port

-

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

As US tensions churn, new generation of protest singers meet the moment

-

Venezuelans eye economic revival with hoped-for oil resurgence

-

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

Samsung Electronics posts record profit on AI demand

-

Formerra to Supply Foster Medical Compounds in Europe

-

French Senate adopts bill to return colonial-era art

French Senate adopts bill to return colonial-era art

-

Tesla profits tumble on lower EV sales, AI spending surge

-

Meta shares jump on strong earnings report

Meta shares jump on strong earnings report

-

Anti-immigration protesters force climbdown in Sundance documentary

-

Springsteen releases fiery ode to Minneapolis shooting victims

Springsteen releases fiery ode to Minneapolis shooting victims

-

SpaceX eyes IPO timed to planet alignment and Musk birthday: report

-

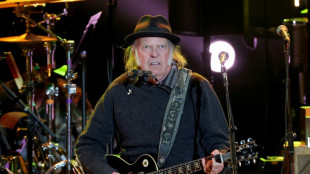

Neil Young gifts music to Greenland residents for stress relief

Neil Young gifts music to Greenland residents for stress relief

-

Fear in Sicilian town as vast landslide risks widening

-

King Charles III warns world 'going backwards' in climate fight

King Charles III warns world 'going backwards' in climate fight

-

Court orders Dutch to protect Caribbean island from climate change

-

Rules-based trade with US is 'over': Canada central bank head

Rules-based trade with US is 'over': Canada central bank head

-

Holocaust survivor urges German MPs to tackle resurgent antisemitism

-

'Extraordinary' trove of ancient species found in China quarry

'Extraordinary' trove of ancient species found in China quarry

-

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

-

UK proposes to let websites refuse Google AI search

UK proposes to let websites refuse Google AI search

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran threatens tough response

-

Germany cuts growth forecast as recovery slower than hoped

Germany cuts growth forecast as recovery slower than hoped

-

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

-

Greenland dispute is 'wake-up call' for Europe: Macron

Greenland dispute is 'wake-up call' for Europe: Macron

-

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

-

Sweden plans to ban mobile phones in schools

Sweden plans to ban mobile phones in schools

-

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

-

Susan Sarandon to be honoured at Spain's top film awards

Susan Sarandon to be honoured at Spain's top film awards

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

-

Spain eyes full service on train tragedy line in 10 days

Spain eyes full service on train tragedy line in 10 days

-

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

-

SKorean chip giant SK hynix posts record operating profit for 2025

SKorean chip giant SK hynix posts record operating profit for 2025

-

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

-

Uganda's Quidditch players with global dreams

Uganda's Quidditch players with global dreams

-

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

-

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

-

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

The eye-opening science of close encounters with polar bears

It's a pretty risky business trying to take a blood sample from a polar bear -- one of the most dangerous predators on the planet -- on an Arctic ice floe.

First you have to find it and then shoot it with a sedative dart from a helicopter before a vet dares approach on foot to put a GPS collar around its neck.

Then the blood has to be taken and a delicate incision made into a layer of fat before it wakes.

All this with a wind chill of up to minus 30C.

For the last four decades experts from the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI) have been keeping tabs on the health and movement of polar bears in the Svalbard archipelago, halfway between Norway and the North Pole.

Like the rest of the Arctic, global warming has been happening there three to four times faster than elsewhere.

But this year the eight scientists working from the Norwegian icebreaker Kronprins Haakon are experimenting with new methods to monitor the world's largest land carnivore, including for the first time tracking the PFAS "forever chemicals" from the other ends of the Earth that finish up in their bodies.

An AFP photographer joined them on this year's eye-opening expedition.

- Delicate surgery on the ice -

With one foot on the helicopter's landing skid, vet Rolf Arne Olberg put his rifle to his shoulder as a polar bear ran as the aircraft approached.

Hit by the dart, the animal slumped gently on its side into a snowdrift, with Olberg checking with his binoculars to make sure he had hit a muscle. If not, the bear could wake prematurely.

"We fly in quickly," Oldberg said, and "try to minimise the time we come in close to the bear... so we chase it as little as possible."

After a five- to 10-minute wait to make sure it is asleep, the team of scientists land and work quickly and precisely.

They place a GPS collar around the bear's neck and replace the battery if the animal already has one.

Only females are tracked with the collars because male polar bears -- who can grow to 2.6 metres (8.5 feet) -- have necks thicker than their heads, and would shake the collar straight off.

Olberg then made a precise cut in the bear's skin to insert a heart monitor between a layer of fat and the flesh.

"It allows us to record the bear's body temperature and heart rate all year," NPI researcher Marie-Anne Blanchet told AFP, "to see the energy the female bears (wearing the GPS) need to use up as their environment changes."

The first five were fitted last year, which means that for the first time experts can cross-reference their data to find out when and how far the bears have to walk and swim to reach their hunting grounds and how long they rest in their lairs.

The vet also takes a biopsy of a sliver of fat that allows researchers to test how the animal might stand up to stress and "forever chemicals", the main pollutants found in their bodies.

"The idea is to best represent what bears experience in the wild but in a laboratory," said Belgian toxicologist Laura Pirard, who is testing the biopsy method on the mammals.

- Eating seaweed -

It has already shown that the diet of Svalbard's 300 or so bears is changing as the polar ice retreats.

The first is that they are eating less seals and more food from the land, said Jon Aars, the lead scientist of the NPI's polar bear programme.

"They still hunt seals, but they also take eggs and reindeer -- they even eat (sea)grass and things like that, even though it provides them with no energy."

But seals remain their essential food source, he said. "Even if they only have three months to hunt, they can obtain about 70 percent of what they need for the entire year during that period. That's probably why we see they are doing okay and are in good condition" despite the huge melting of the ice.

But if warming reduces their seal hunting further, "perhaps they will struggle", he warned.

"There are notable changes in their behaviour... but they are doing better than we feared. However, there is a limit, and the future may not be as bright."

"The bears have another advantage," said Blanchet, "they live for a long time, learning from experience all their life. That gives a certain capacity to adapt."

- Success of anti-pollution laws -

Another encouraging discovery has been the tentative sign of a fall in pollution levels.

With some "bears that we have recaptured sometimes six or eight times over the years, we have observed a decrease in pollutant levels," said Finnish ecotoxicologist Heli Routti, who has been working on the programme for 15 years.

"This reflects the success of regulations over the past decades."

NPI's experts contribute to the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) whose conclusions play a role in framing regulations or bans on pollutants.

"The concentration of many pollutants that have been regulated decreased over the past 40 years in Arctic waters," Routti said. "But the variety of pollutants has increased. We are now observing more types of chemical substances" in the bears' blood and fatty tissues.

These nearly indestructible PFAS or "forever chemicals" used in countless products like cosmetics and nonstick pans accumulate in the air, soil, water and food.

Experts warn that they ultimately end up in the human body, particularly in the blood and tissues of the kidney or liver, raising concerns over toxic effects and links to cancer.

Y.Ponomarenko--CPN